Whose Bodies Were They?: Enshrining Relics of the Buddhas and Saints in Eleventh Century China

Seunghye Lee

Ph.D. candidate, University of Chicago

Friday, December 2, 4-6 p.m. CWAC 156

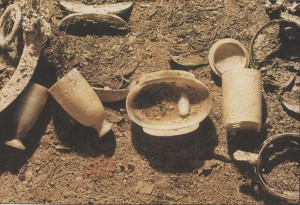

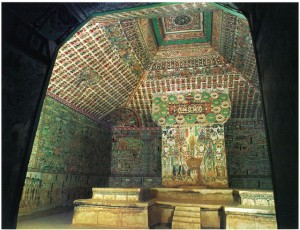

In Chinese Buddhist sources, the term “relics” is often modified by other terms, implying the particular nature of the body present in the relics. This paper will investigate how the “remnant body relics,” one of such terms, was conceptualized and materialized in the relic deposit of the Ruiguang Monastery Pagoda in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. A reliquary set, named Jeweled Pillar of the Remnant Bodies of All the Buddhas and Saints 諸佛聖賢遺身舍利寶幢 (1013 C.E.) from the deposit will be the focus of this presentation. I will examine two crucial issues that have been overlooked in past scholarship: what the relics are and how the relics relate to the reliquary set. Acknowledging the impossibility of tracing the sources of the relics, I would rather examine the identity of the relics, given in the inscriptions, against the discourses and practices of relics in Tang-Song China. My investigation reveals that this entity, composed of relics and reliquaries, exemplifies a crucial change that had occurred in the cult of relics from the eighth century onward. It demonstrates a more inclusive notion of relics that encompasses relics of the Buddhas and those of the monastic dead culled from funerary pyre. The relationship between the two, I argue, was complementary. When they were deposited together, the relics of the Buddha certainly lent sacredness to the relics of eminent monks. Yet the influx of monastic type contributed to the continued cult of the jewel-type relics of the Buddha, alongside the cult of palpably corporeal type that came to prevail in China since the eighth century. The pivotal factor orchestrating such a fusion was the shared materiality of the two: radiant jewels that were thought to be capable of wonders. The identity of the relics seems to have guided the designer of the Jeweled Pillar to choose a motif that had never been incorporated into the reliquary: a statue of the monk Sengqie (617-710) whose divine status elevated from a monk to a saint, and a Buddha who had left grains of jewel-like relics by the eleventh century. The strategic positioning of the Sengqie image within the pillar-cum-pagoda was intended to provide not only a symbolic protection but also visual sanctification for the relics enshrined.